Crypto Series: WWII – Enigma

With this post we're leaving classical pencil and paper ciphers and getting into the mechanic ciphers used during the World War II era. We're gonna see the most famous of the cipher machins, the Enigma machine used by the Germans. Our analysis will be based on the book Applied Cryptanalysis from Mark Stamp and Richard M. Low. A very recommendable book if you are interested on cryptanalysis, really.

The Enigma Machine

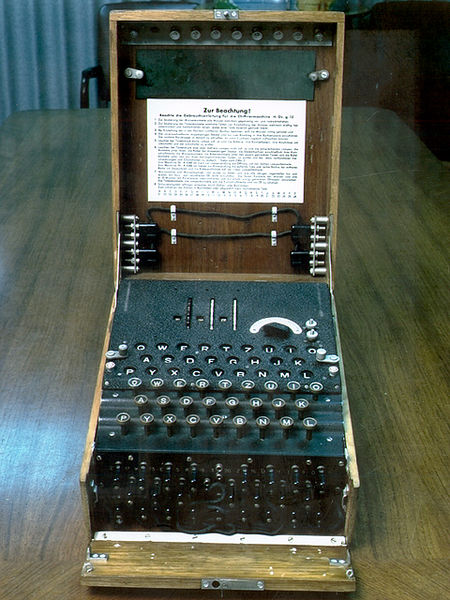

The Enigma machine was developoed and patented by Arthur Scherbius in 1918, and was adopted by the nazi Germany for military and diplomacy use. Polish cryptanalysts broke the Enigma cipher in the late 1930s, and Allieds exploited this knowledge during WWII.

Máquina Enigma

It is said that thanks to Enigma being broken without the Germans noticing it (thanks to the more or less careful use of the obtained intelligence) the WWII was shortend one year or even more. There has been a lot of writing around Enigma, and I'm not an expert in the field, so I refer you to Google if you want more historical information 🙂

Encrypting and decrypting with Enigma

To encrypt with Enigma, after initializing the machine with the key as we'll see later, one simply had to press the plaintext letter to encrypt in the keyboard, and then the corresponding ciphertext letter would be enlightened in the upper (back-lighted) keyboard.

To decrypt, one had to set the machine into the corresponding state and press the received ciphertext letter. Then, in the upper keyboard the plaintext letter would get enlightened.

Enigma's features

Enigma was an electro-mechanical machine, based on the use of rotors. In the previous figure, one can easily see the mechanical keyboard and the back-lighted keyboard, which worked as input and output of the device.

Further, there is what seems to be a switchboard (stekker in German) with cables connecting one of the ends with another, and three rotors in the upper side of the machine. The configuration of these rotors and the cables of the stekker are the initial key of the machine.

Once the machine was initialized, it was possible to press in the keyboard the plaintext or ciphertext letters and obtain the ciphertext or the plaintext respectively. The workings of the machine were essantially as follows:

After pressing a key in the keyboard, a signal was sent through the corresponding stekker pin. Thanks to the cable configuration, this signal was transmitted to a different letter. Thus, the stekker worked as a mapping in the alphabet, where each letter was substituted by another one: a simple substitution.

Rotores de la máquina Enigma

After it, the signal went through the three rotors, reflected in the reflector and went back through the rotors (see figure). Finally, from the rotors it went again through the stekker, which performed a new substitution, and turned on the backlight of the corresponding letter. The net effect of the rotors and the reflector was again a permutation: each letter was converted into a different one.

However, if this were it, we would have no more than a simple substitution, with the only complexity of the use of an electromechanical machine. What Enigma added was a variation of the disposition of these rotors.

Each time a key was pressed, the rightmost rotor stepped one position. The middle rotor stepped in an odometer-like fashion, each time the rightmost rotor went through all of its steps. The leftmost rotor stepped in the same way, but depending on the middle rotor.

Further, it was possible to select the point where each rotor would step. This means that it could be when the previous rotor reached the initial position, but it could be in a different position. We could set it, for instance, to step when the previous rotor had stepped 5 times. From there on, it would step every time the initial rotor was in that position.

Therefore, Enigma was a cipher where each letter was encrypted with a different simple permutation of the alphabet... but with an enormous number of possible permutations.

For a more detailed analysis of the Enigma machine, please refer to the aforementioned book, where the way the machin works is analysed, the key space size (i.e. number of possible keys) is computed and an attack is presented.

Crypto Series: Vigenère’s Cipher (2)

As I promished, we're gonna see a different method to obtain the key length used to encrypt a text using Vigenère's algorithm. This is a method somewhat more difficult to understand than Kasiski's method, since it requires some mathematical analysis to obtain the recipe.

Friedman's test or the incidence of coincidences

This method, discovered by William F. Friedman in the 1920s, is based on computing the index of coincidences of the cryptogram's letters. The idea is that for two random letters from the cryptogram to be the same, there is a possibility that they were also the same in the original plaintext if the number of letters they have in between is a multiple of the key length.

Basically, we'll take the X first letters of the cryptogram and the X last letters, and count the number of coinciding letters in the same position. Finally, we'll divide this number by the number of letters taken and then we will have the index of coincidence.

Considering a source providing independent characters with the frequency distribution of English, and uniformly distributed characters for the key (i.e. all letters with the same frequency, 1/26 for the English alphabet), we have that:

- The probability that any two letters are the same is approximately 0.0385 when X is not a multiple of the key length

- The probability that any two letters are the same is approximately 0.0688 when X is a multiple of the key length.

So, with this process wi can determine that high values for the index of coincidence will mean that the shifted distance X is a multiple of the key length, and this way we will determine the most likely key length.

Let's see how we get these probabilities, so that we are able to obtain them in case of having a language different than English. We simply have to consider that for any two ciphertext characters and

to coincide, the following relation must hold:

Then, we consider two different cases: if L divides i-j, then , since in that case we have that

. So, the probability for this case is:

However, when i-j is not a multiple of L, then for the two ciphertext characters to be equal the following equation needs to hold

But as we said before, the distribution of key characters is uniform, and therefore this probability is:

That's it for today. This time there is no example, but stay tuned cause we'll see an exercise soon 🙂

And I hope next week I'm able to post some practical exercise using Cryptool to analyze a Vigenère cipher or something alike.

Crypto Series: Classical ciphers

During some posts we're gonna get introduced into classical ciphers. From Wikipedia, "a classical cipher is a type of cipher used historically but which now have fallen, for the most part, into disuse".

This post will study one of the most known classical ciphers, the Caesar cipher, and other similar ciphers.

Caesar Cipher

Caesar's cipher, named after Julius Caesar, is a substitution cipher that simply substitutes each letter by the letter K positions to the right in the alphabet. So, for a K value of 3, A would be encrypted as D, B as E, C as F and so on.

In mathematical terms, considering an alphabet with 26 letters, where A would be letter 0 and Z letter 25, we can define these encryption and decryption operations as:

Where means reducing the result modulo 26, or in simpler terms, if the result is above or below the 0-25 range, we would add/subtract 26 as many times as needed to make it fall into this range.

As you can see, very simple. For instance, if we encrypt the sentence CRIPTOGRAFIA PARA TODOS under key 5, we get the following ciphertext: HWNUYTLWFKNF UFWF YTITX.

Here we can already see one of the weaknesses of this cipher: the structure of the plaintext remains. As you can see, last word in the message starts with a Y, then it has two T's, one I and one X. Therefore, we know that this word has the second and fourth letter identical. Also second and fourth letters are identical in the second word, but different to the ones in the last word.

This, in a large text and within a context, could lead us to decipher great part of the text. For instance, knowing that it's a text about information security, we can try to find words with the same structure as security or information and map these letters for all the text. With this, we would have parts of other words, and with some luck we would be able to obtain more letters by guessing those words. Continuing like this, at the end we would have the complete text.

Another tool that allows us to easily analyse this kind of ciphers is frequency analysis, which we mentioned previously. If we take a text encrypted using this system and count the number of appearances of each letter, and then obtain (or generate) a table of relative frequencies for the target language, we can match the most frequent letter in the ciphertext and the most frequent letter in the target language.

Then, since the same shift is applied to all the letters, we would have the key and would be able to obtain the complete message. In case of getting a non-sense message, we could try with the second most frequent letter instead of the first one. Since it's a statistical analysis, it's possible that the character distribution in our text doesn't completely match the original distribution, but will certainly be similar.

Simple substitution ciphers

Caesar's cipher we just analysed is one of the so-called simple substitution ciphers, which always substitute each symbol of the input alphabet by a given symbol of the output alphabet.Besides Caesar's cipher, Atbash cipher is another quite famous substitution cipher, where each the alphabet is inverted: A->Z, B->Y, ... Y->B, Z->A.

But not only these two simple substitution ciphers exist. We can create any modification of the input alphabet as output alphabet. Even then, all these ciphers suffer from the same problem: the structure is maintained and they are quite easy to break using frequency analysis and word matching.

Example: Breaking a simple substitution cipher

This time I encrypted an English text. This is how the ciphertext looks like:

ZL VAGRERFGF NOBHG FRPHEVGL ERYNGRQ GBCVPF UNIR QEVSGRQ N YVGGYR OVG, ZBIVAT SEBZ CHER FBSGJNER NAQ ARGJBEXVAT FRPHEVGL GB PELCGBTENCUL NAQ CENPGVPNY NGGNPXF BA PELCGBTENCUVP VZCYRZRAGNGVBAF, YVXR FVQR PUNAARY NANYLFVF NGGNPXF.

VA GUVF EROBEA OYBT V JVYY GEL GB VAGEBQHPR GUR ERNQREF VAGB GURFR GBCVPF JVGUBHG TRGGVAT VAGB GBB PBZCYRK ZNGUF. GUR NVZ VF GB CEBIVQR NA HAQREFGNAQVAT BS PELCGBTENCUL JVGUBHG UNIVAT ERNQREF YBFG BA ZNGURZNGVPNY PBAPRCGF. LBH JVYY GRYY JURGURE V NPUVRIR GUVF TBNY BE ABG.

Looks pretty complicated, doesn't it? Let's see how to approach this example, assuming this is a simple substitution cipher. First of all, we're gonna count how many times appears each letter, and then divide it by the total number of letters. I've done it with this simple program I quickly coded, although it's possible to do it with Cryptool but I don't have it available right now.

Once it's done, we sort it by frequency. For instance, copy-pasting the output of the program into a spreadsheet in Google Docs and pressing order by the corresponding column. The top 3 letters are:

G 52 0.124402

R 38 0.090909

V 37 0.088517

So, we go to a frequency table for English (here) and see that E is the most frequent letter in this language. Now we subtract 'G'-'E'=7. If we apply this key using a Caesar's cipher, we just get garbage. However, if we take 'R' as 'E, then 'R'-'E'=13. Deciphering using Caesar's cipher, we get:

MY INTERESTS ABOUT SECURITY RELATED TOPICS HAVE DRIFTED A LITTLE BIT, MOVING FROM PURE SOFTWARE AND NETWORKING SECURITY TO CRYPTOGRAPHY AND PRACTICAL ATTACKS ON CRYPTOGRAPHIC IMPLEMENTATIONS, LIKE SIDE CHANNEL ANALYSIS ATTACKS.

IN THIS REBORN BLOG I WILL TRY TO INTRODUCE THE READERS INTO THESE TOPICS WITHOUT GETTING INTO TOO COMPLEX MATHS. THE AIM IS TO PROVIDE AN UNDERSTANDING OF CRYPTOGRAPHY WITHOUT HAVING READERS LOST ON MATHEMATICAL CONCEPTS. YOU WILL TELL WHETHER I ACHIEVE THIS GOAL OR NOT.

Much more readable 🙂 Don't you recognize it? Look at http://www.limited-entropy.com/en/about 🙂

We've decrypted the text, although not at our first try, but at our second. Another option would have been using 'G' as 'T', since T is the second most frequent letter in English. The result is exactly the same.

However, facing an unknown transformation, we would have been to play with other hints besides frequency analysis. For instance, we could use the fact that we expected to see CRYPTOGRAPHY in the text, and assign this word to the only word in the ciphertext that has the same letter in the third and the last position. Then, we would substitute all its letters in the ciphertext and would see if it makes any sense.

From there, we just need to continue on guessing letters... kind of a puzzle 🙂

That's it for today, I hope you're liking it :). Questions and comments are more than welcome!

Crypto Series: Classification of Attacks

As a quick note on the cryptographic systems description on the previous post, I'd like to mention that atacks to cryptosystems are usually classified based on the information known to the cryptanalyst. The basic types of attacks are:ásicos son:

- Ciphertext-only: The cryptanalyst knows only the ciphertext, and often also some information about the context of the message.

- Known-Plaintext: The cryptanalyst knows pairs of plaintexts and corresponding ciphertexts.

- Chosen-Plaintext: The cryptanalyst is able to choose plain texts and obtain their corresponding ciphertexts.

- Chosen-Ciphertext: The cryptanalyst can choose any ciphertext and obtain its corresponding plaintext.

Although the final two kinds could seem to be identical, there is a big difference mainly when applied to public key algorithms. In these algorithms, it is usually very easy to encrypt any plaintext. Thus, these algorithms need to withstand chosen-plaintext attacks. However, a chosen-ciphertext attack would require a decryption oracle, which would return any ciphertext decrypted without exposing the decryption key.

Crypto Series: Introduction – Basic Concepts

Before getting into matter, we're gonna see the basic concepts on which great part of the text is going to relay on. Don't be scared, they are very basic :-). These are the definitions:

Cryptography is the science studying information protection, both unauthorized accesses/uses and modification of the information. Cryptography is only about using algorithms to protect this information, while Cryptanalysis is about studying techniques to break this protection, those algorithms designed by cryptographers. It's clear that both sides are intimately related, and both of them are grouped in what is known as Cryptology.

A Cryptosystem is made of the following components:

- Messages: The group of all the messages that one can encrypt. Also known as plaintext.

- Ciphertexts: The group of all encrypted messages.

- Keys: The group of all the secrets that can be used to obtain a ciphertext from a plaintext.

- Encryption and Decryption algorithms: The algorithms or transformations that need to be applied to a plaintext in order to convert it into a ciphertext or back, using a secret key.

Un Criptosistema o Sistema Criptográfico consta de los siguientes componentes:

- Mensajes: Es el conjunto de todos los mensajes que se pueden cifrar. El llamado texto en claro o plaintext.

- Criptogramas: El conjunto de todos los mensajes cifrados. En inglés llamado ciphertext.

- Claves: El conjunto de secretos que se pueden utilizar para obtener un criptograma en base a un mensaje.

- Algoritmos de cifrado y descifrado: Los algoritmos o transformaciones necesarias para convertir un mensaje en su correspondiente criptograma y viceversa, haciendo uso de una clave secreta.

So, given a cryptosystem with its encryption algorithm, which we denote as , and its corresponding decryption algorithm (

), the following equation must hold:

Where k y k' are the corresponding encryption and decryption keys. These keys might be identical (symmetric crypto) or different (asymmetric crypto), as we'll see later.

This means that when you decrypt a message encrypted under key K using its corresponding decryption key K', you obtain the original message. Obvious, isn't it?

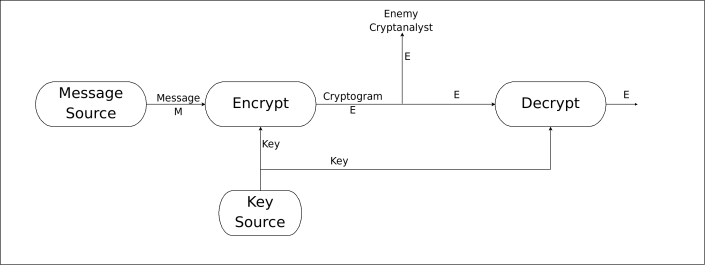

The figure below shows the conventional cryptosystem as depicted by C.E. Shannon in its book Communication Theory and Secrecy Systems.

Cryptosystem scheme

Finally, to finish this post about basic concepts, we'll see how to statistically characterize a message source. Statistical characterization of a language is a quite powerful tool on its own when it's about analyzing a cipher, specially in case of basic ciphers as we'll see in the next post.

Let's imagine a message source that produces messages in a given language, for instance Spanish. We can try to characterize the source by means of the probability that a certain character appears in the text, independent of the rest of the text.

Thus, a character c would appear with a probability . With this characterization, the word hola would appear with a probability of:

A slightly more powerful option would be characterizing the language as a series of bi-grams (i.e. groups of two characters) with a given probability. In this case, the word hello would have the following probability:

However, this option besides being an identical concept to the former one, requires of much bigger frequency tables and more effort to characterize the message source.

A question that might arise now is how would we manage to obtain a table of relative frequencies for each one of the letters. Basically, we would take a sufficiently large text in the given language and count the number of times each letter appears. Then we divide this number by the total of letters in the text, and get its relative frequency. Frequency tables can be seen in Frequency Analysis [Wikipedia].

Next time we'll see how this frequency characterization with independent charactes can be useful to break basic ciphers.

Book Review: The IDA Pro Book

[DISCLAIMER: Este post va en inglés puesto que el libro también es en inglés... y a quien le interese lo entenderá]

At the beginning of last month I ordered a copy of The IDA Pro book from Chris Eagle at Amazon. Since reversing has been one of my pending subjects for a while now, and after seeing it recommended by Ilfak's himself, I decided to buy the book. I've just finished my first reading of the whole book, and before going into applying the acquired knowledge I've thought it may be useful to share my opinion with you.

The book is divided into 5 different parts. Part I, Introduction to IDA, covers the very basis about disassembling, reversing and reversing tools, and IDA Pro.

Part II, Basic IDA usage, introduces the reader into the IDA world in chapters 4 to 10. After introducing the user interface and the different IDA displays, Chir Eagle goes into disassembly navigation and manipulation, data types, cross-references and graphing, and finally the different IDA flavours apart from the normal Win32 GUI version (console mode for Windows,Linux,OS X). Chapter 8 about datatypes and data structures also provides a nice covering of C++ reversing, showing how to locate vtables and explaining inheritance relationships among others.

Part III, Advanced IDA usage, extends the IDA knowledge provided in the previous part by discussing its configuration files, library recognition methods, how to extend IDA's knowledge about library functions and, although it is not its main purpose, what can IDA do for us if we want to patch a binary.

Part IV of the book discusses the available options to extend IDA's functionality: IDC scripts, the IDA SDK, plug-in development and processor and loader modules. To be honest, I skipped a big chunk of this part because I believe it is not worth now. I'll just come back to these chapters once I start disassembling things and needing to tailor IDA's functionality to my needs.

Part V discusses how to deal with real-world problems. It starts with a chapter about the different assembly code produced by different compilers for the same source code, and then goes into a very interesting description about obfuscated code analysis (from the static analysis perspective mainly). Next, Eagle gives some hints on how to use IDA for finding vulnerabilities and provides a list of several useful real-world IDA plugins.

Last part of the book, Part VI, discusses the IDA debugger and its integration with the disassembler. This part starts with an introduction chapter, continues with a discussion on its integration with the disassembler and ends with a chapter about remote debugging with IDA.

As you have seen, this book provides a thorough coverage of IDA's capabilities, and gives real world examples. The examples, together with the IDC and plug-in code, make it a very interesting reading for those willing to learn about reversing and about the most popular disassembler these days.

If you'd like to learn how to use IDA efficiently, how to tailor it to your needs and automate your static analysis tasks, this is your book. Definitely, it is worth the money if you want to get into IDA and have a good reference book.

El malingo presenta Reto Hacking IX

El maligno ha anunciado que esta noche, a las 20:00, empieza el Reto Hacking IX. El reto cuenta con 10 niveles, y los premios además de puntuar en la general de los retos hacking de este año, son estos (copia-pega de la entrada del maligno):

- Primero: La gloria, la fama, el honor de hacer un solucionario y responder a una entrevista para el lado del mal. Además, una cena y unos cubatas en tu ciudad (como gane quién yo me sé va a ir a Zurich la madre del topo) que quedará para la historia con fotos que no querras-que-vean-tus-descencientes.

UPDATE: El primero se llevará el Badge de la Defcon16

- Segundo: El honor de ser el primer Luser, el gran perdedor, el perdedor oficial. El título honorífico de ser el Luser del Reto Hacking IX y sí, una cena, pero las copas las pagas tú que para eso deberías haber ganado.

UPDATE: El segundo se llevará tres pegatas de la Defcon16

- Tercero: A ti te voy a regalar un libro de hacking para que sigas practicando y así alcances la gloria de ser el campeón o de ser el No Luser.

UPDATE: El tercero se llevará una pegata de la Defcon16

Yo si tengo tiempo me pondré a ratos, aunque en un plazo de una semana presento el PFC y luego vienen fiestas del pueblo, así que no estaré muy libre para ponerme...

Suerte a los que os decidáis!

EDITADO: Ayer estuve pegandole un ratillo cuando llegué a las 9, un poquitín más después de cenar y otro rato cuando volví de dar una vuelta por ahí. La cosa va de romper CAPTCHA's, pasé los niveles 1-5 pero el 6 se me resiste... no veo NADA de momento 😳 .

Las soluciones las estoy haciendo con PHP con libcURL, reutilizando un script que usé en la CampusParty de 2006 (creo). Te suena Javi? xD Esta vez toca hacer cosas 'parecidas' pero hay que saltarse el captcha 1000 veces en 60 minutos, con lo que automatizarlo es clave (y un coñazo la espera xD).

EDITADO 2: Pues ya hay ganador. Kachakil acaba de alzarse con la victoria y con los 10 puntos... el tío está en el top en todos los retos. Enhorabuena desde aquí!

Jane: pruebas seguridad Campus Party 2008

En este post voy a recopilar las soluciones de las pruebas del concurso de la Campus Party, las correspondientes a la categoría de seguridad. Pongo todo de mi memoria y de los logs del chat de equipo, así que no tengo los enunciados ni binarios ni nada... espero que quede más o menos claro todo 🙂 El orden tampoco es 100% seguro que sea ese, pero es más o menos como nosotros lo hicimos.

Verificación de protocolos criptográfico: modelando objetivos

Seguimos con la serie de verificación de protocolos, después de los anteriores:

Ahora nos toca ver cómo completamos nuestros modelos mediante la inclusión de los objetivos del protocolo en ellos. En spi-calculus, para modelar el objetivo de confidencialidad simplemente usamos aserciones ( secrecy assertions en inglés ). Las aserciones son mecanismos que no modifican el flujo del modelo ( no influyen en la semántica operacional ) y simplemente indican que un agente espera que un determinado valor se mantenga secreto. Por ejemplo, podríamos escribir:

Pa = new s; ( secret(s) | out net {s}kab)

Pb= inp net x; decrypt x is {s}kab; secret(s)

De esta forma, se especifica que ambos agentes creen que s es un secreto.

Por otra parte, para especificar opciones de autenticidad nos valemos de aserciones de correspondencia ( correspondence assertions ). Esto simplemente significa que el agente que inicia la autenticación iniciará la aserción de correspondencia con unos parámetros, y el que la acaba la finalizará. Para que todo vaya bien, si existe una finalización debería haber existido antes una inicialización con los mismos parámetros.

Espero que se vea mejor con este ejemplo tomado de los apuntes de Cristian Haacks como una narración informal:

A begins! Send (A, m, B)

A ? S : A, {B, m}kas

S ? B : {A, m}kbs

B ends Send (A, m, B)

Así pues, decimos que es seguro si no existe la posibilidad de que se ejecute el B ends Send(A,m,B) sin que antes e haya ejecutado un A begins! Send(A,m,B). Para acabar, el ! indica que esta aserción se repite indefinidas veces, es decir que un evento begin puede corresponderse con un end repetidas veces. Un ejemplo de esto sería una firma digital, puesto que la firma se puede comprobar muchas veces y siempre será válida. Sin embargo, a veces interesa que solo se de una vez, para garantizar la frescura de la información y evitar replay attacks.

Para ello, se usan eventos inyectivos, que se modelan sin el ! y simplemente un begin puede corresponderse con un end, y nunca más. Para conseguir esto, los protocolos hacen uso de números de secuencia, nonces (number used once), timestamps o similares.

Realmente hay un poco más de chica por aquí detrás con cómo se propagan estos eventos por los canales y demás, pero vamos a dejarlo en que se considera seguro si esto ocurre, ya que en caso contrario significaría que el atacante puede forzar a B a ejecutar un end Send(A,m,B) sin que realmente A haya mandado el mensaje B, lo cual viola la autenticación.

También hay un poco más de teoría respecto a Spi-calculus y procesos seguros respecto a confidencialidad, que especifica qué procesos se pueden denominar así. Intuitivamente, son aquellos procesos en los que no existe ninguna manera de llegar a algo que escriba un secreto en un canal público mediante la semántica operacional de spi-calculus.

Ahora bien, después de este rollo, cómo nos lo montamos con ProVerif para especificar estas propiedades? Pues es bastante sencillo:

Las metas de confidencialidad, simplemente se especifican en la zona de declaraciones con una query tal que así:

query attacker: s.

Donde s es el valor que queremos que sea secreto. El problema es que ProVerif usa macros y los nombres son globales, así que si creamos dos nombres iguales en distintos procesos y hacemos una query, irá para los dos. Además, si usamos variables para las queries, siempre dará que el atacante puede obtenerlo mientras que no es necesariamente cierto.

Para este caso, lo que podemos hacer es generar un flag único y pedir a ProVerif que nos diga si el flag puede obtenerse. Por ejemplo, imaginemos la variable M que ha sido obtenida mediante tras leer de la red. Si queremos que sea secreta, deberíamos hacer algo como:

query attacker: M.

process (*otro_proceso*)|(in(net,M))

Pero entonces ProVerif nos dirá que el atacante puede obtener M, ya que es una variable. Lo que haríamos sería:

query attacker:flagM.

process (*otro_proceso*)|(in(net,M);out(M,flagM);)

En este caso, si el atacante puede conocer M podrá leer del canal M, con lo que podrá obtener el flag y la query fallará. Si no, no podrá obtener el flag y no fallará.

Por otra parte, las aserciones de correspondencia se transforman en eventos, y podemos especificar que un evento debe estar precedido por otro. Un ejemplo sacado de mis códigos de ProVerif sería:

query evinj : endSendToInit(x,y,z) ==> evinj : beginSendToInit(x,y,z).

query evinj : endSendToResp(x,y,z) ==> evinj : beginSendToResp(x,y,z).

query evinj : endAckToInit(x,y,z) ==> evinj : beginAckToInit(x,y,z).

query evinj : endAckToResp(x,y,z) ==> evinj : beginAckToResp(x,y,z).

Aquí estamos diciendo que el evento endSendToInit(x,y,z) debe estar precedido por el evento beginSendToInit(x,y,z), y lo mismo para el resto de eventos. La palabra clave evinj indica que se trata de una correspondencia inyectiva, es decir uno a uno. Si usaramos ev en su lugar se trataría de correspondencia no inyectiva, muchos a uno.

Por último, comentar que es posible especificar en ProVerif la propiedad de no interferencia ( non-interference ), que significa que un atacante no será capaz de distinguir una ejecución del protocolo de otra cambiando los valores de las variables de las que deseamos preservar dicha propiedad.

Dicho más sencillo: que no se puede obtener ninguna información de las variables, ni siquiera si son iguales o distintas de una ejecución a la otra. Por ejemplo, esto no cumpliría dicha propiedad:

P(x) = out(net,{x}k);

Puesto que si {x1}k es igual a {x2}k, entonces x1 es igual a x2. Para resolverlo usaríamos cifrado no determinístico, que simplemente añade una parte aleatoria al mensaje. Algo así:

P(x) = new n; out(net,{(x,n)}k);

De esta forma, como n es aleatorio y presumiblemente diferente cada vez, que el texto cifrado sea igual no implica que el contenido lo sea.

Para especificar esta propiedad, en ProVerif escribiremos por ejemplo:

noninterf x1,x2.

Y luego modelaremos dos procesos en paralelo, uno con x1 y otro con x2. Tras ejecutar ProVerif (que ya veremos cómo se hace en otro post) nos dirá si se puede distinguir entre ellos o no.

Esto es todo de momento... sigo dandoos el coñazo con teoría que puede que no se entienda mucho :oops:, pero en el próximo post explicaré cómo ejecutar ProVerif y un pequeño ejemplo con varias cosas juntas, y después en el siguiente analizaremos el modelo de TLS que puse hace un tiempo.

Si alguien está leyendo esto, que comente si se entiende más o menos o algo 🙂 ( Y quien lo esté leyendo es todo un campeón xD)

Verificación de protocolos criptográficos: Modelado (II)

Continuamos en este post con las técnicas de modelado de protocolos criptográficos. Ahora sí vamos a adentrarnos en el mundo de ProVerif viendo la sintaxis que usa para definir los protocolos.

Un archivo fuente de ProVerif puede estar en spi-calculus o mediante cláusulas de Horn. Nosotros solo vamos a ver spi-calculus entre otras cosas porque yo de cláusulas de Horn ni idea 🙄 . Los archivos fuente .pi tienen varias partes que vamos a ver por separado: